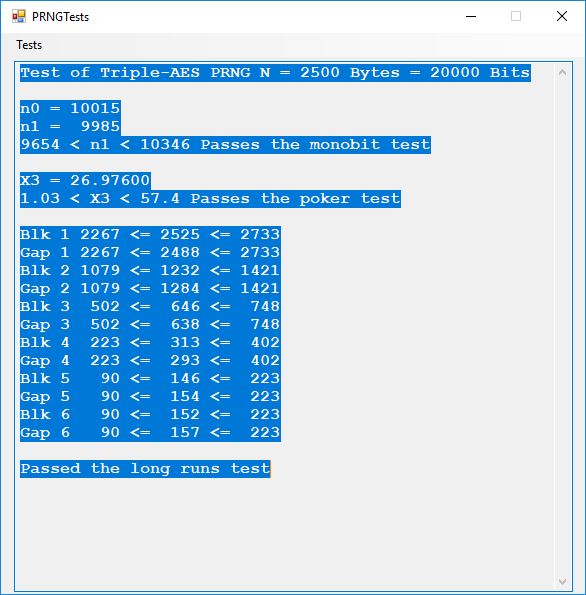

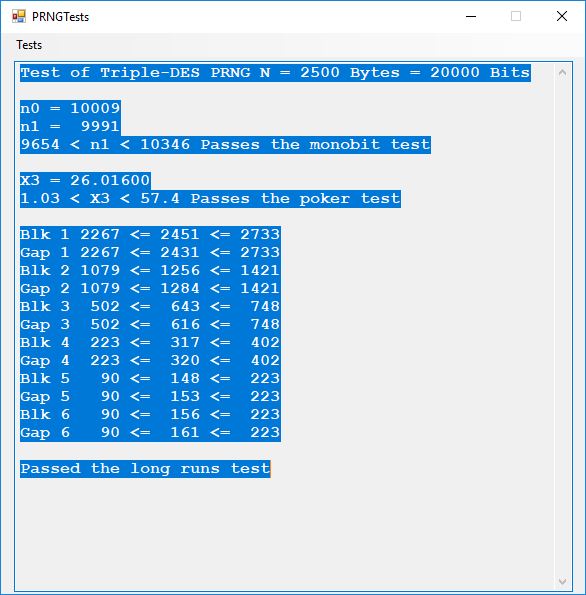

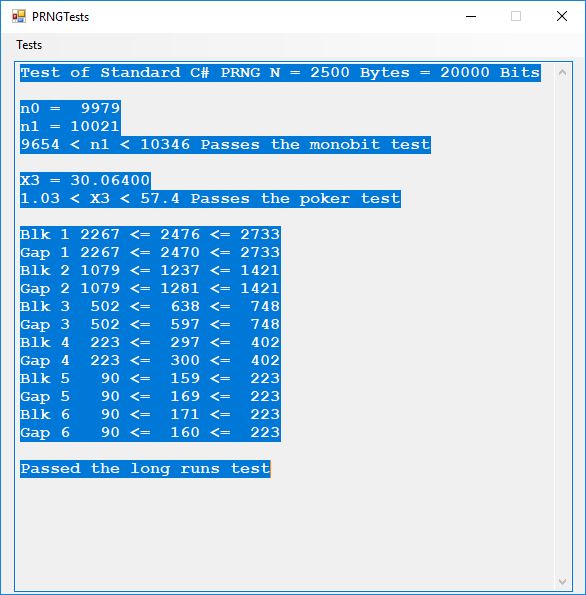

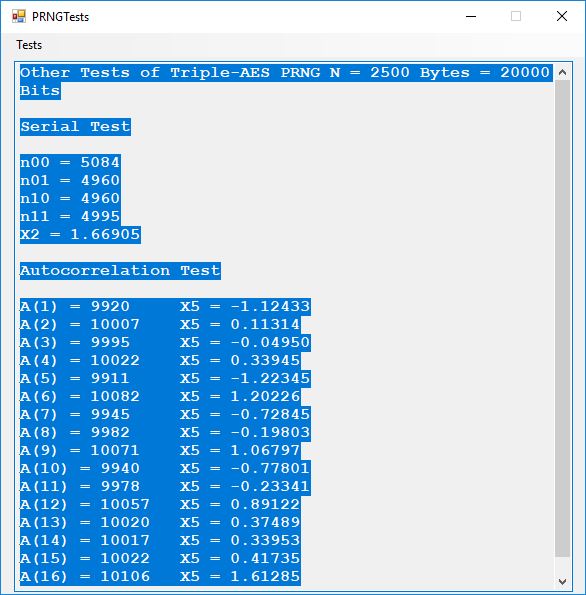

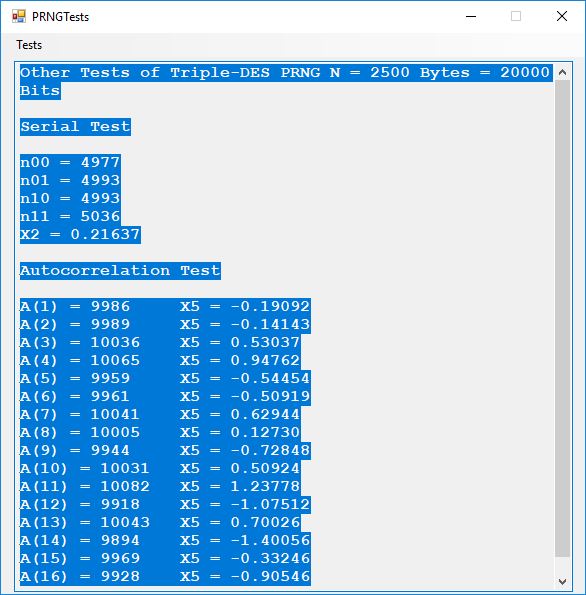

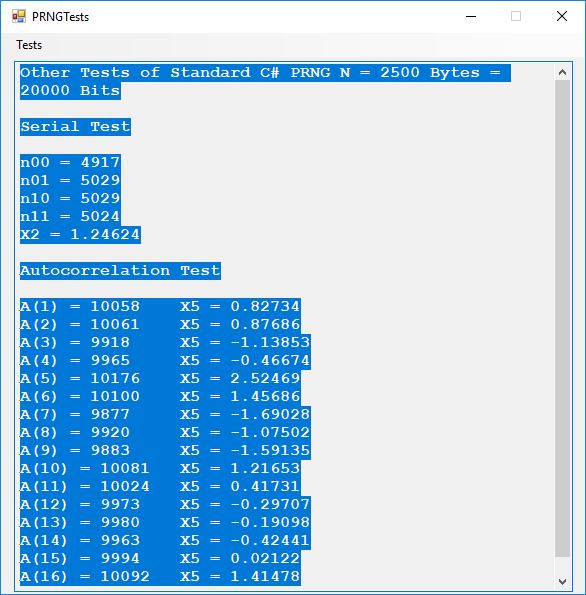

This blog post is dedicated to Section 5.3.1 ANSI X9.17 generator page 173 with 5.11 Algorithm and Section 5.4.4 Five basic tests pages 181-183 especially 5.32 Note of the Handbook of Applied Cryptography by Alfred J. Menezes, Paul C. van Oorschot, and Scott A. Vanstone. I developed a PRNG test program for three PRNGs namely, Triple-AES, Triple-DES, and the C# built-in PRNG.

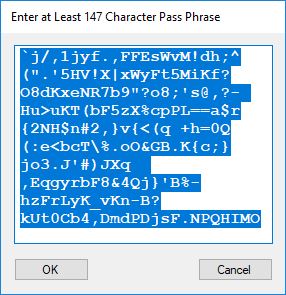

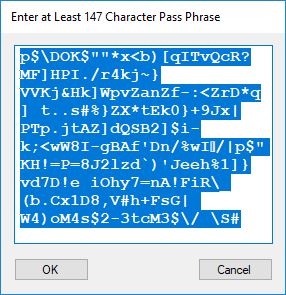

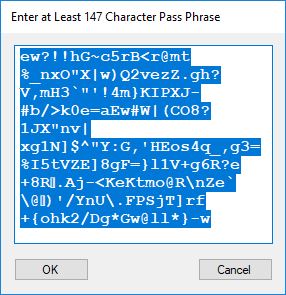

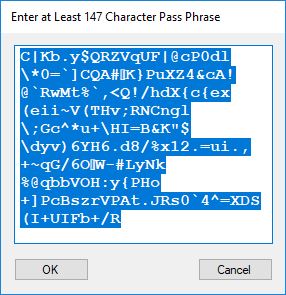

Each time an algorithm is run a randomly generated key is generated based on the time of day and the C# built-in PRNG with a key space of 2147483647 possible seeds. Triple-AES requires a 147 7-bit ASCII key and part of a similar key is used to construct the 296-bit Triple-DES key material. Now onto my C# Windows Forms application’s screenshots.

We use the five basic statistical tests of Chapter 5 Section 5.4.4 which are as follows:

- Monobit Test also Known as the Single Bit Frequency Test

- Serial Test also as the Two-Bit Frequency of Occurrence Test

- Poker Test

- Runs Test (Not to be confused with Montezuma’s Revenge)

- Autocorrelation Test

Below is a copy of a recent email of mine concerning Secret Key Exchange or Distribution:

The linchpin and point of greatest vulnerability in any secret key cryptographic system is the key exchange mechanism. Now suppose that we are living in a post quantum computer world. This means that traditional public key cryptosystems such as RSA (integer factorization problem based) and elliptic curve public key cryptography (discrete logarithm problem based) are effectively broken. That implies that any public key based cryptographic key exchange is compromised over communication channels where Eve, the classical eavesdropper, is listening in on the key exchange between Alice and Bob. Quantum cryptography over fiber optic channels allows the communication endpoints to detect the eavesdropper and thus abort a potentially compromised key exchange. However, quantum cryptography is not readily available everywhere on the vast Internet. The rest of this email missive is devoted to other more exotic means of secret key exchange.

Human to human key exchange is optimal provided that all human beings in the loop are trustworthy. A good way to exchange secret keys is via a diplomatic courier with a diplomatic pouch and the key bits are concealed by a steganographic means.

Now suppose an adversary of an English speaking and reading country has two agents or human intelligence operatives that have infiltrated the country. Further both agents have the same 1024-bit seeded pseudorandom number generator-based stream cipher on their desktops and/or laptops for secure communications. That means they must somehow pass 147 secret 7-bit printable ASCII characters of information between one another for each quasi-one-time pad message. Each character represents 7 bits of the key and there are 5 bits left over after construction of each key. Also, suppose an actual face-to-face meeting between the two spies is inadvisable. Enter the text based social media or library book code. Now suppose the two spies are connected to one another via Facebook but are afraid to use text messaging for direct key exchange or clandestine communication. The solution is to use a shared Facebook page of text to construct the secret key. One spy shares a Facebook post containing at least 147 English characters and the other spy looks up the post. Both spies cut and paste the first 147 English characters of the post into a key constructing application. Voila, now both spies can communicate using their handy dandy stream cipher and email and/or cell phone text messaging of encrypted data in the form of three-digit decimal numbers. An alternative key exchange could be by the classic and readily available book code. Assume both spies have access to the same library, but not concurrent access. Both somehow agree to go and copy 147 characters from the same book in the library’s reference section. They write down the passage and take it home to enter the text into the key generator. Again, we have a means of clandestine key exchange.