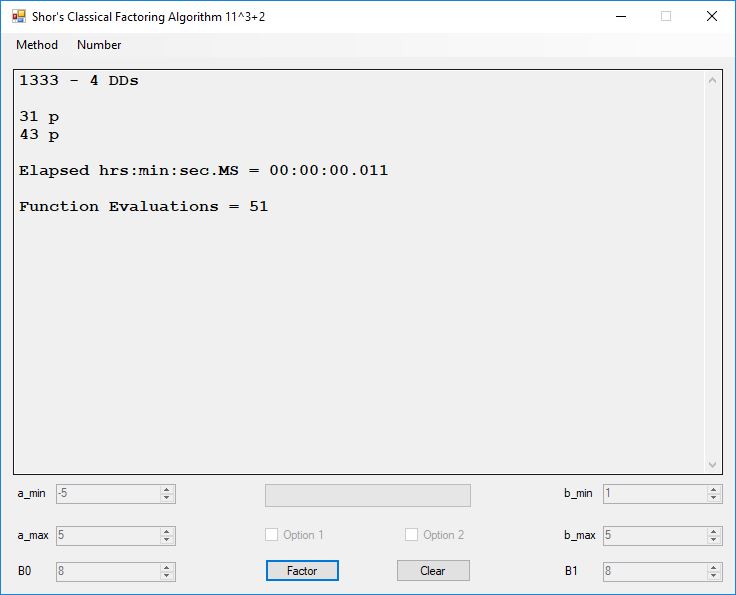

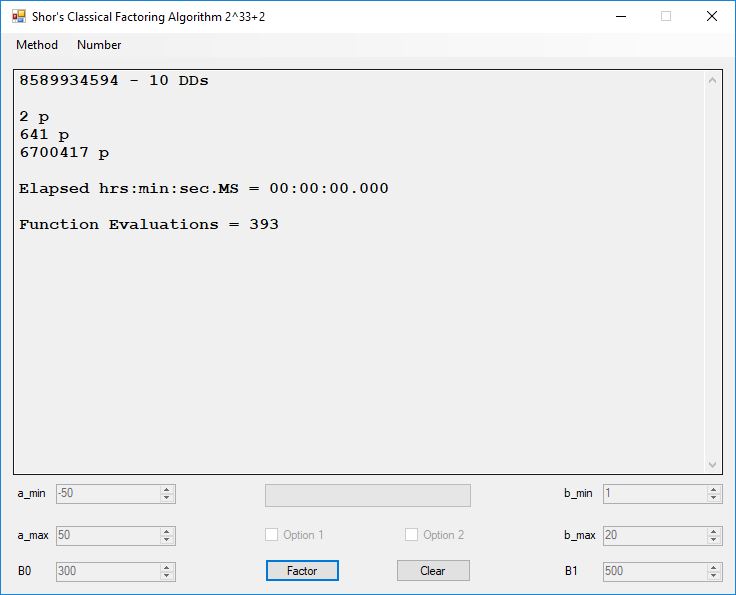

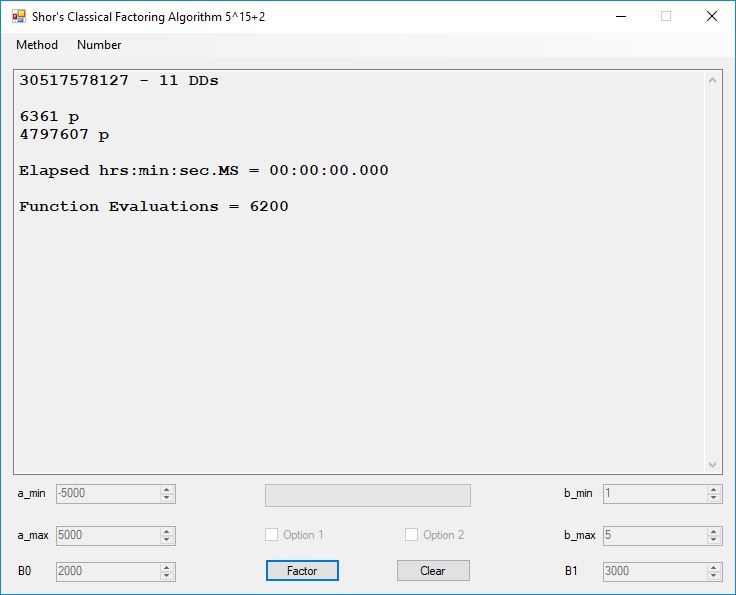

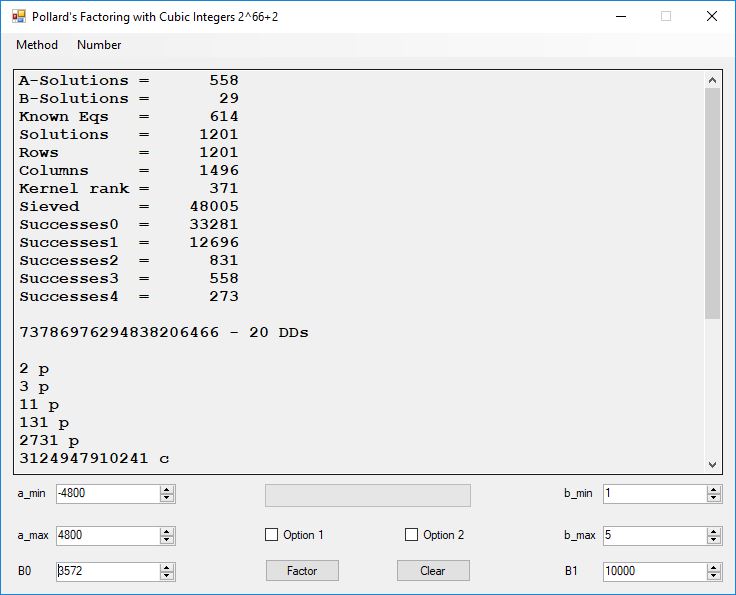

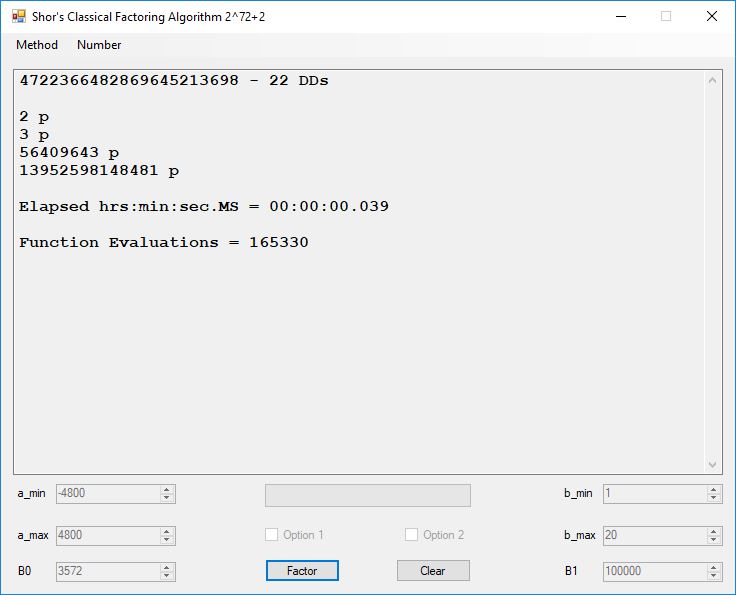

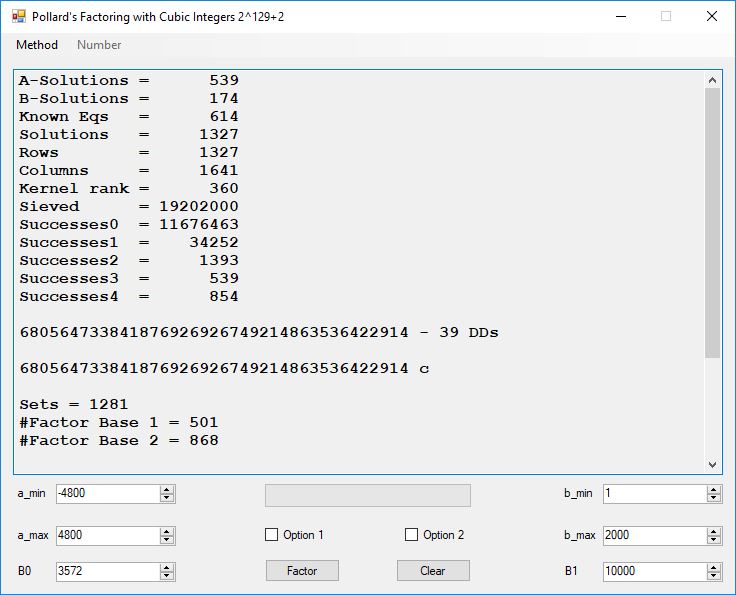

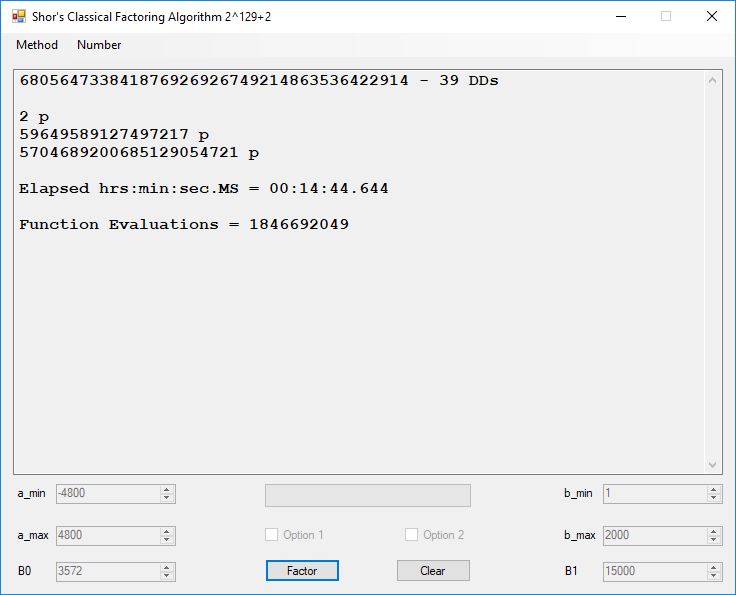

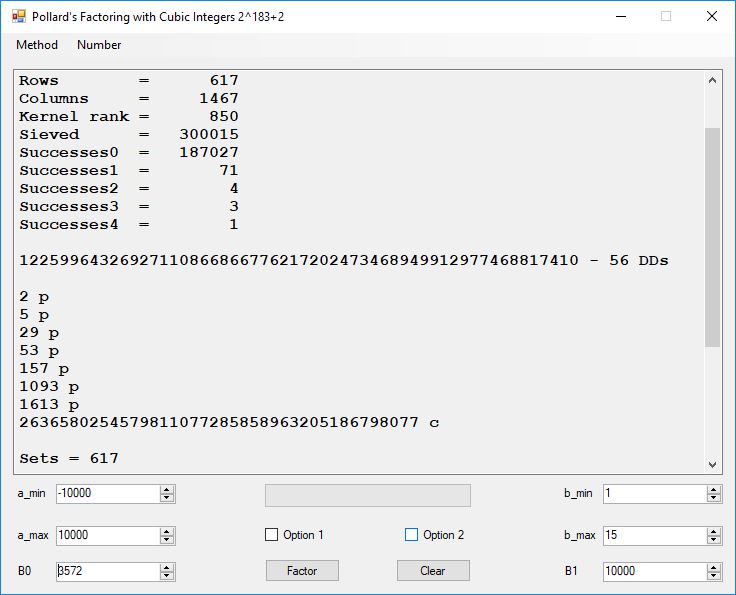

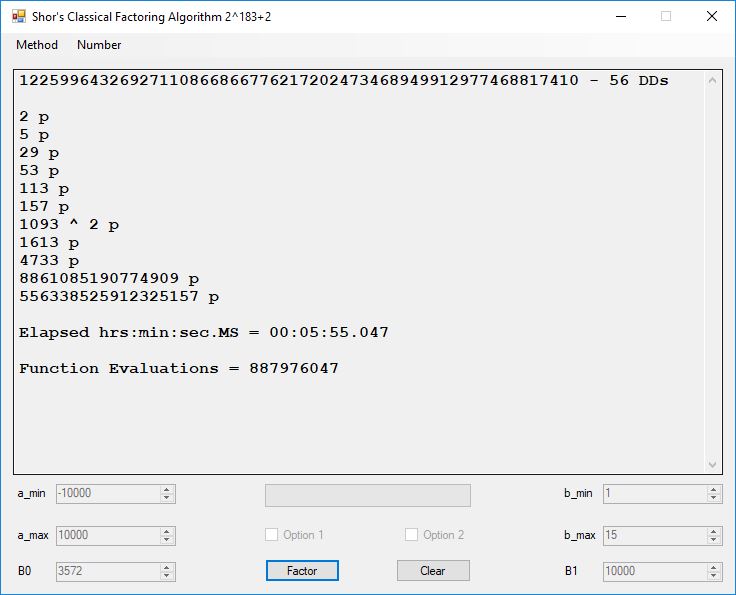

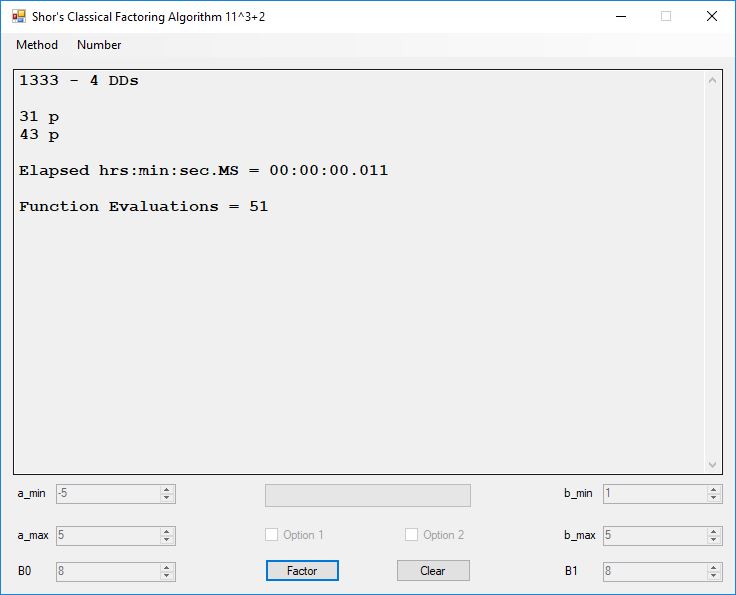

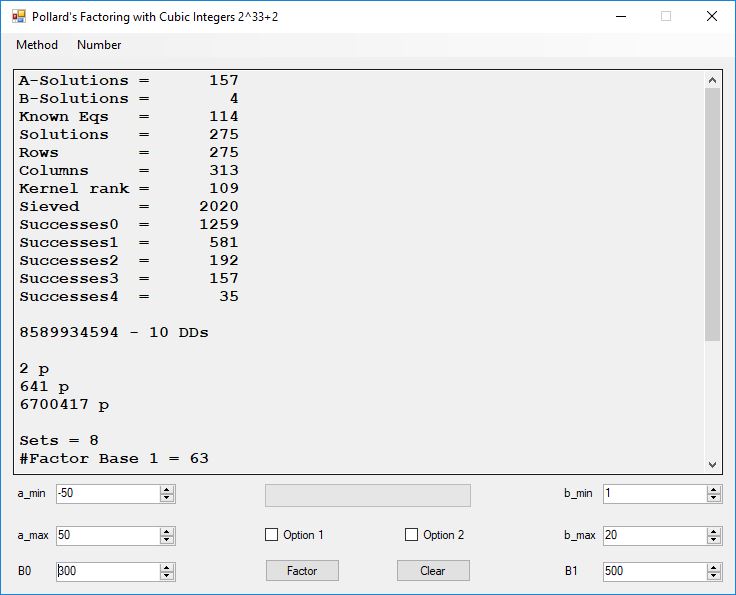

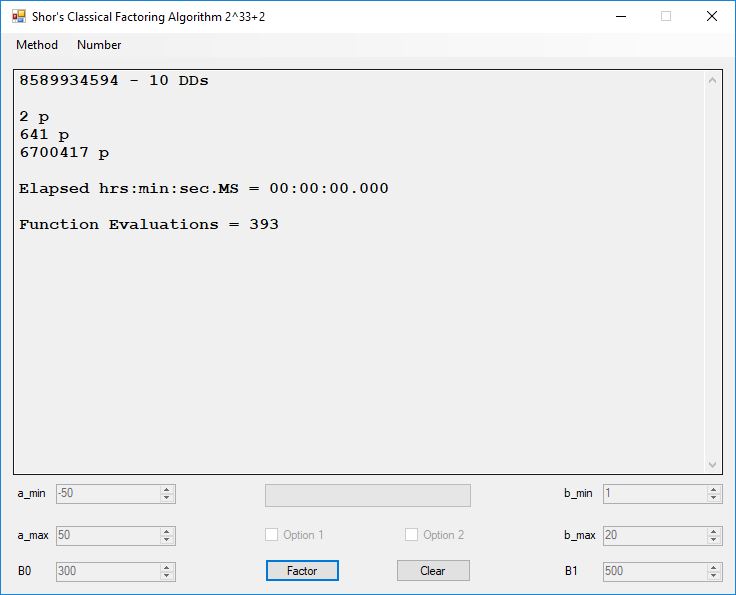

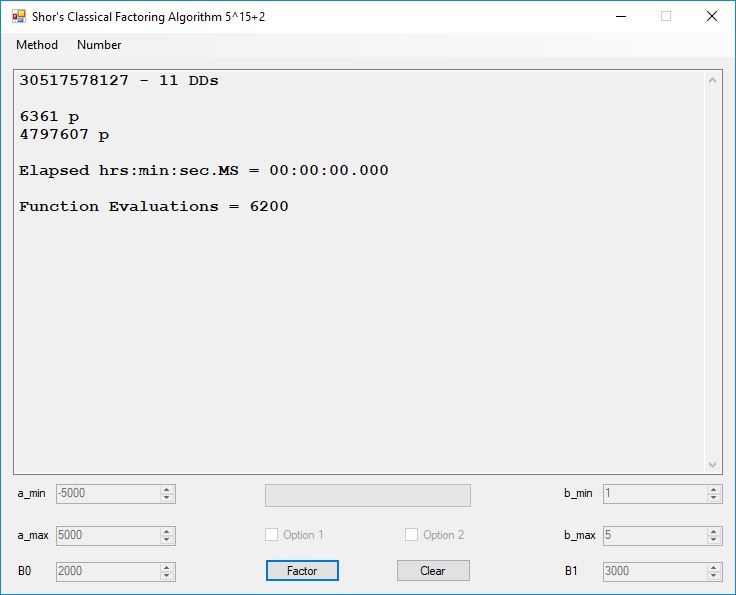

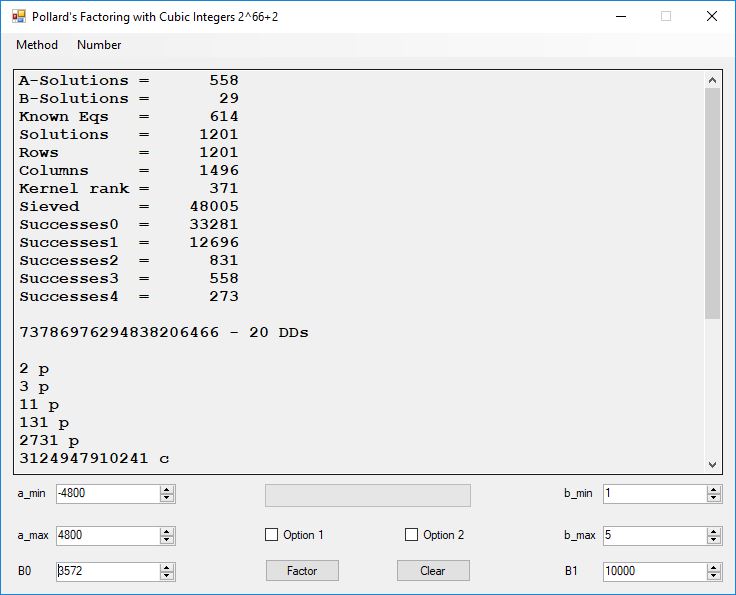

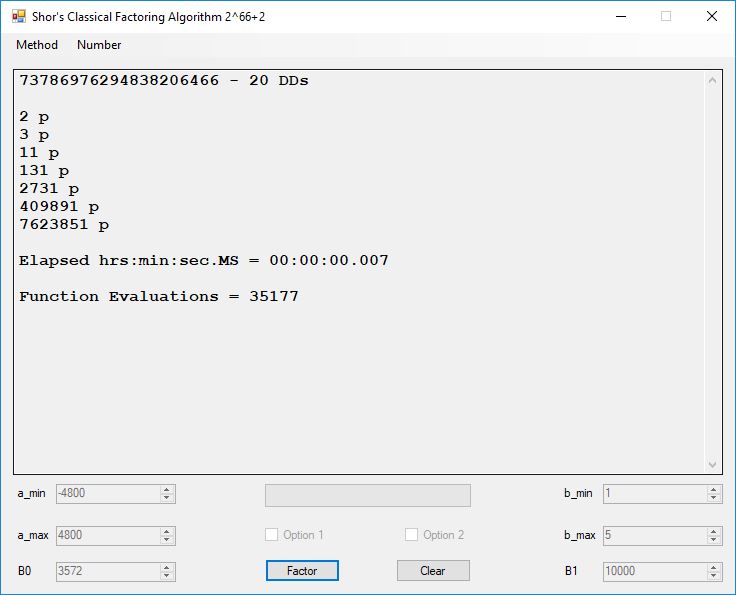

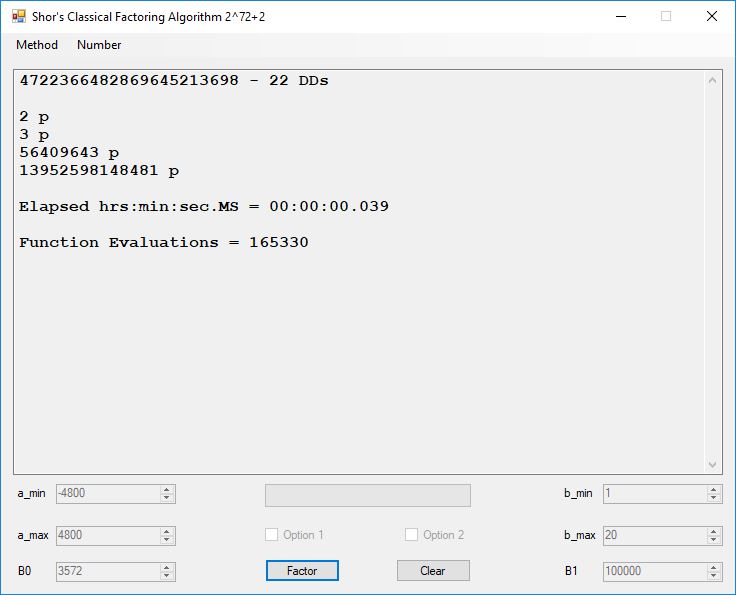

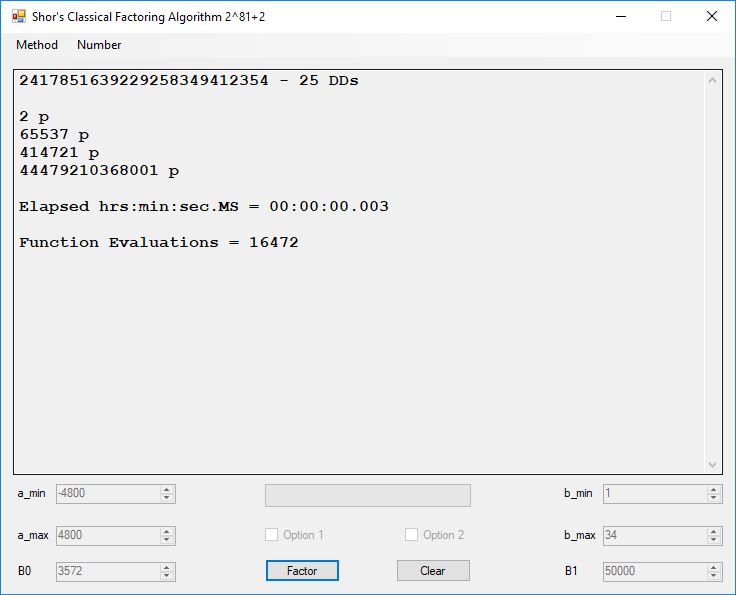

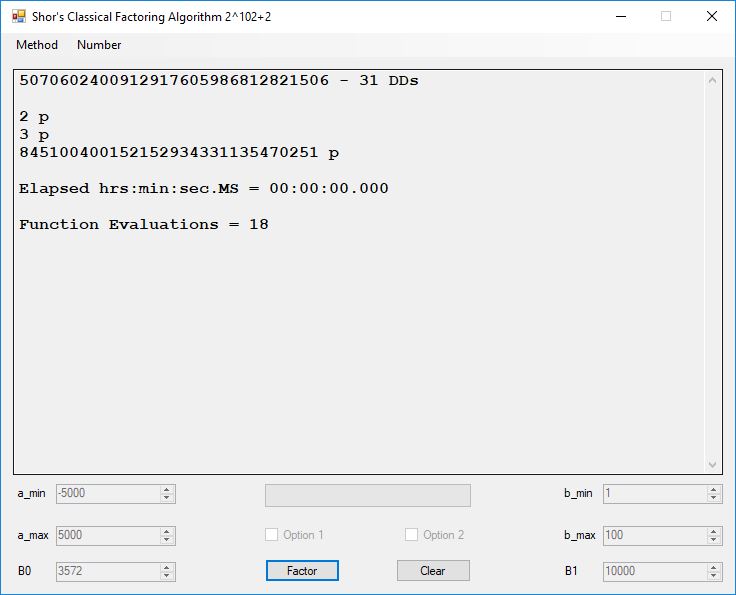

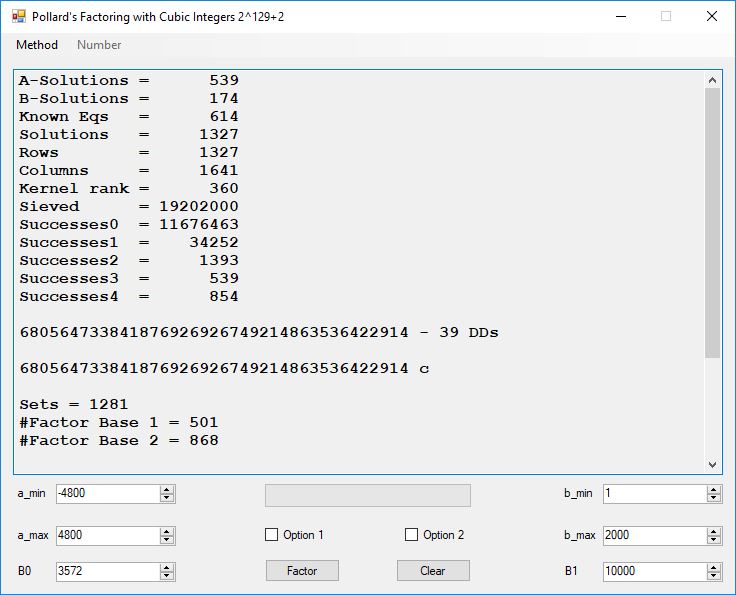

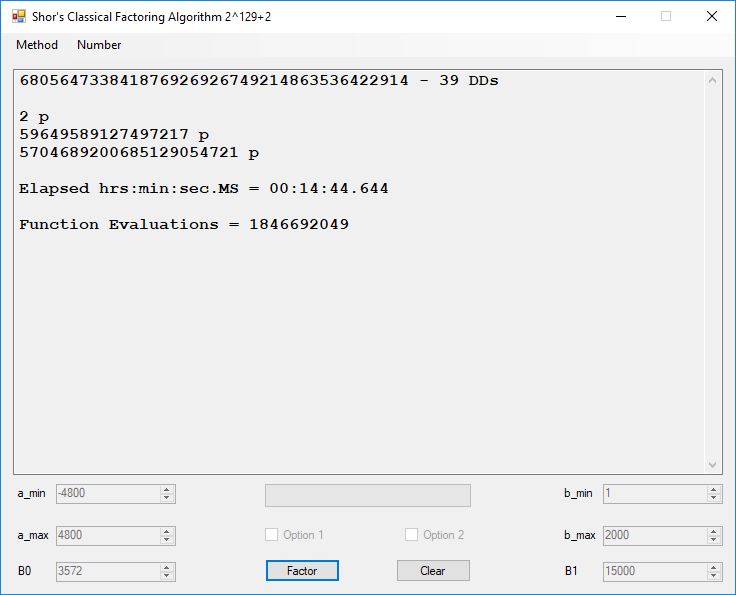

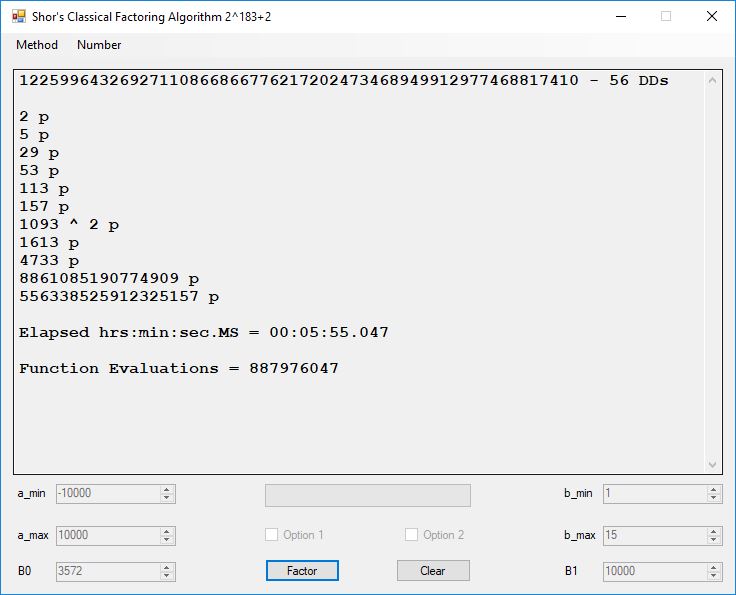

We tried to factor the following numbers with each algorithm: 11^3+2, 2^33+2, 5^15+2, 2^66+2, 2^72+2, 2^81+2, 2^101+2, 2^129+2, and 2^183+2. Shor’s algorithm fully factored all of the numbers. Factoring with cubic integers fully factored all numbers except 2^66+2, 2^71+2, 2^129+2, and 2^183+2.

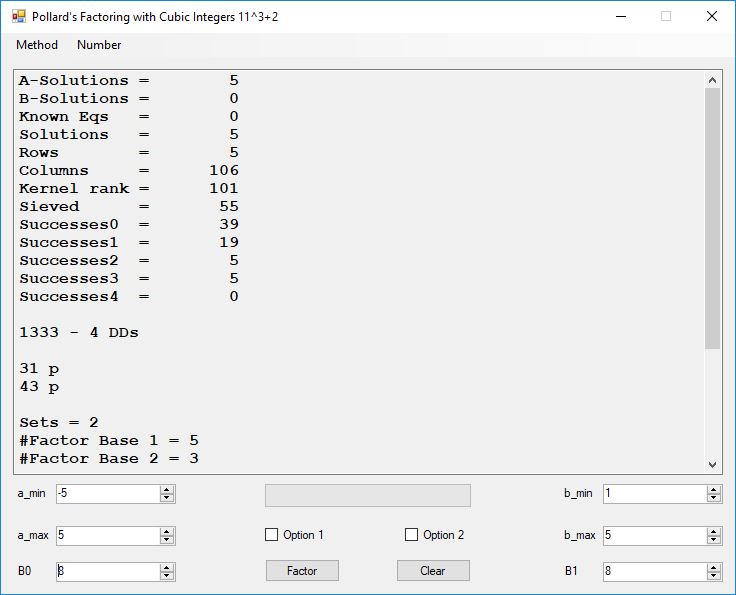

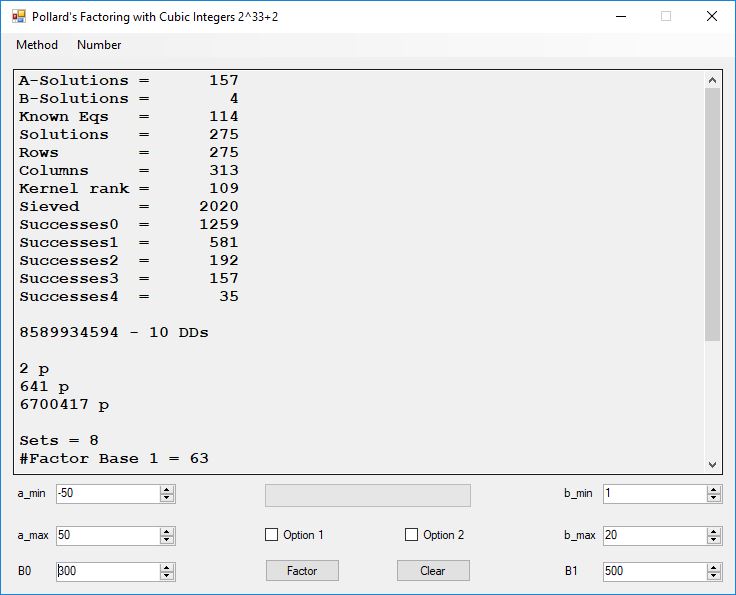

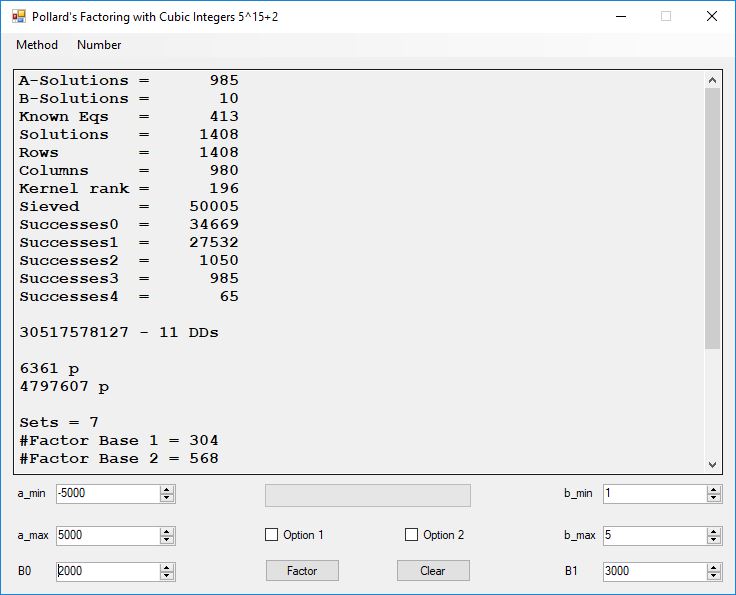

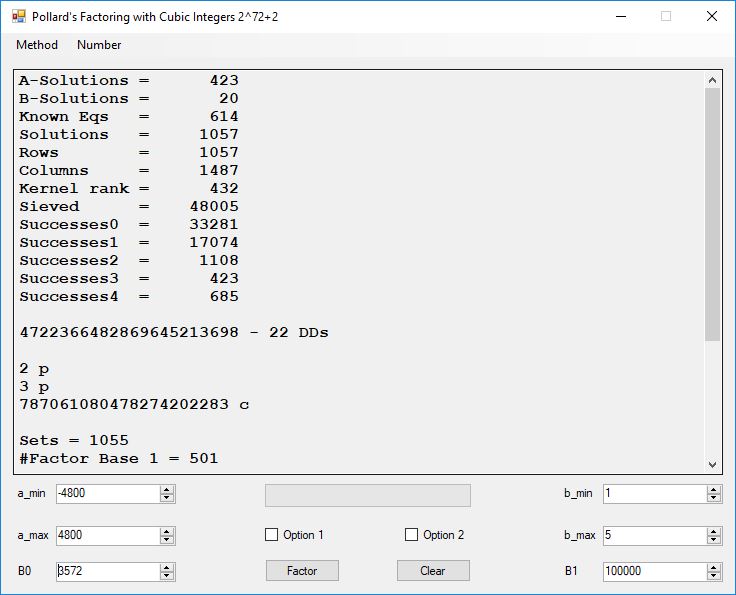

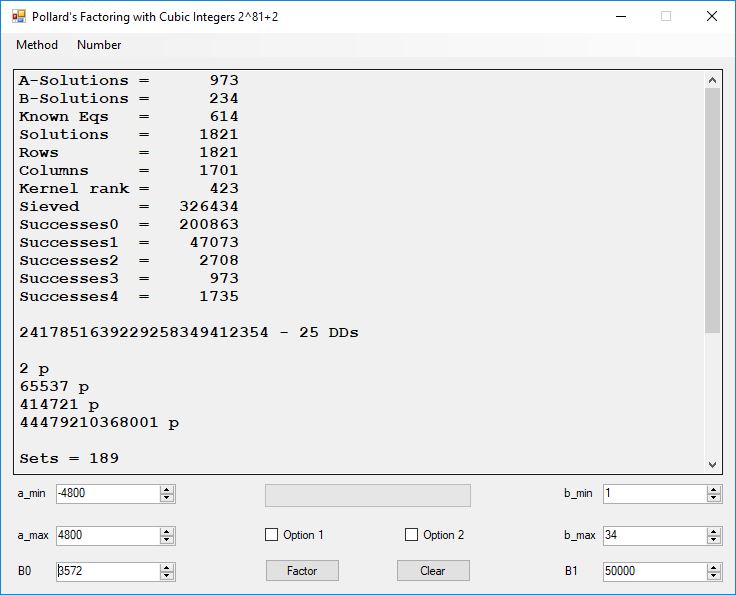

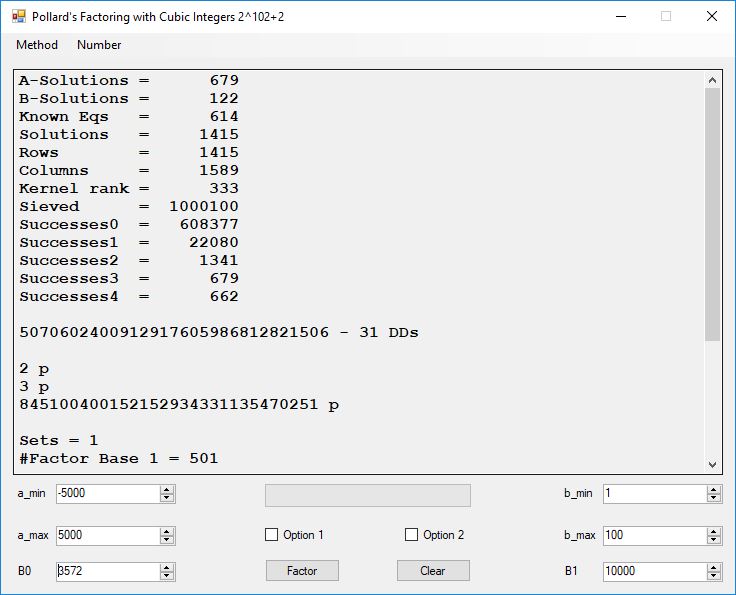

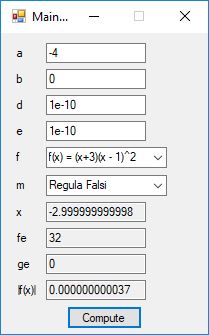

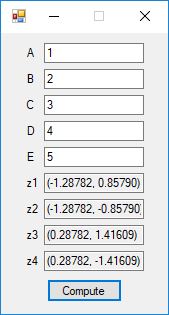

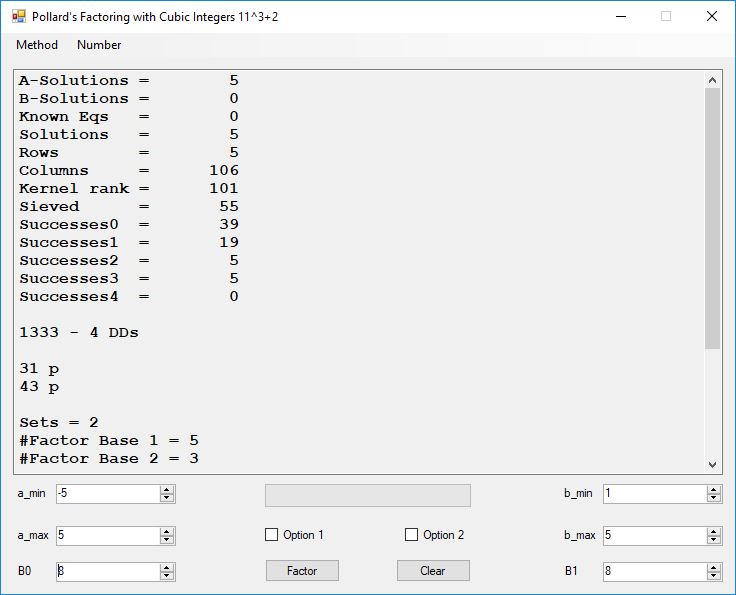

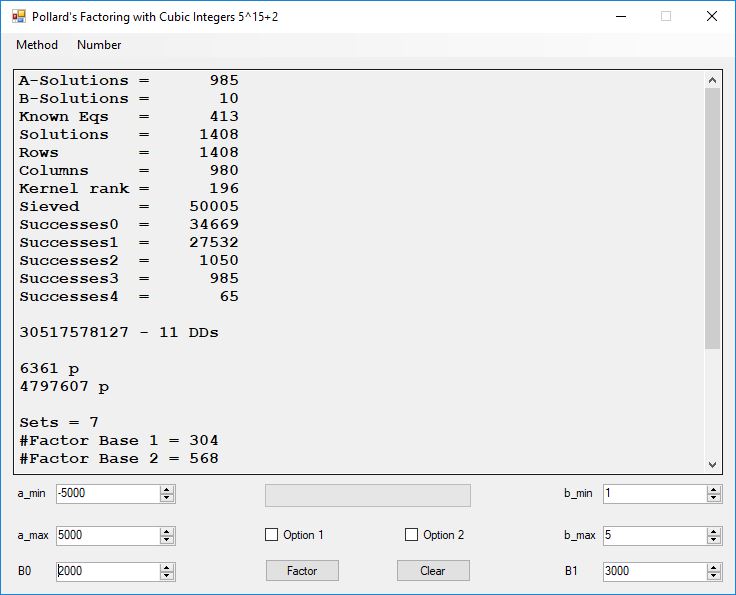

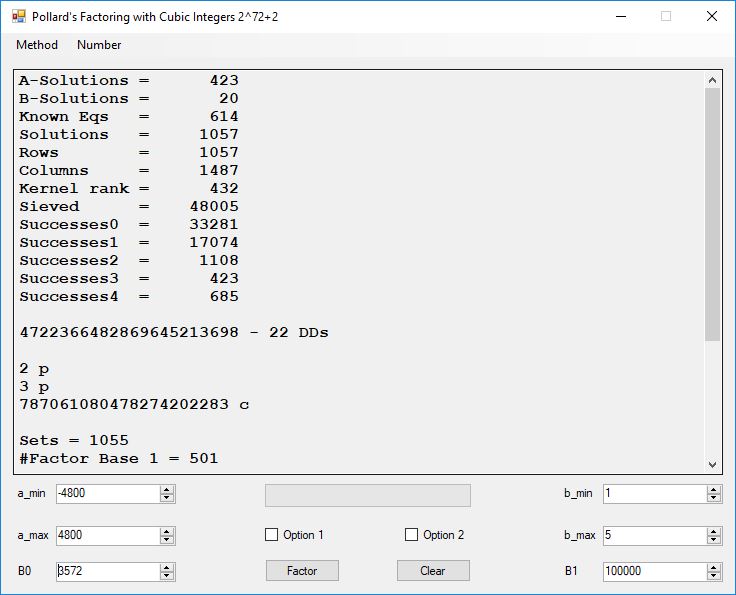

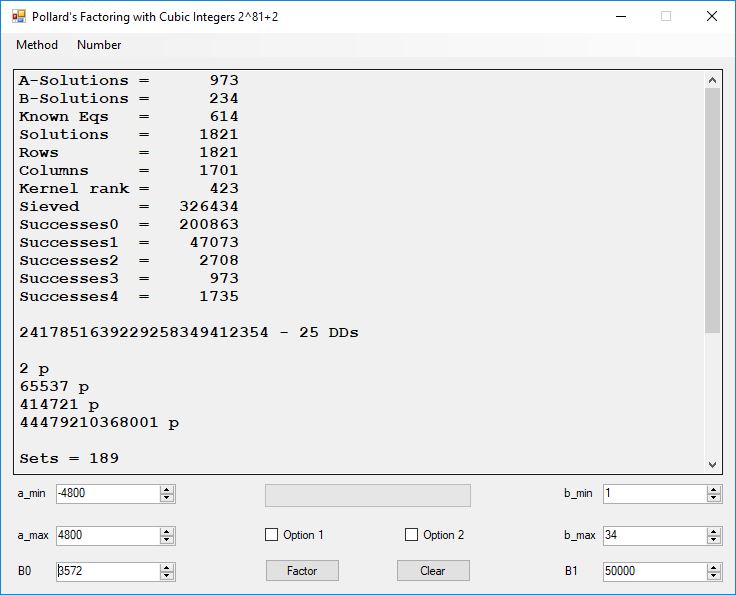

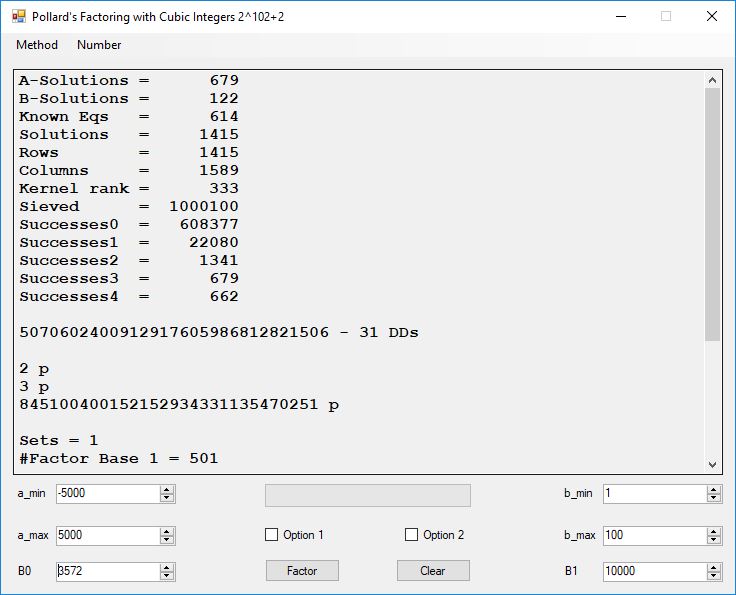

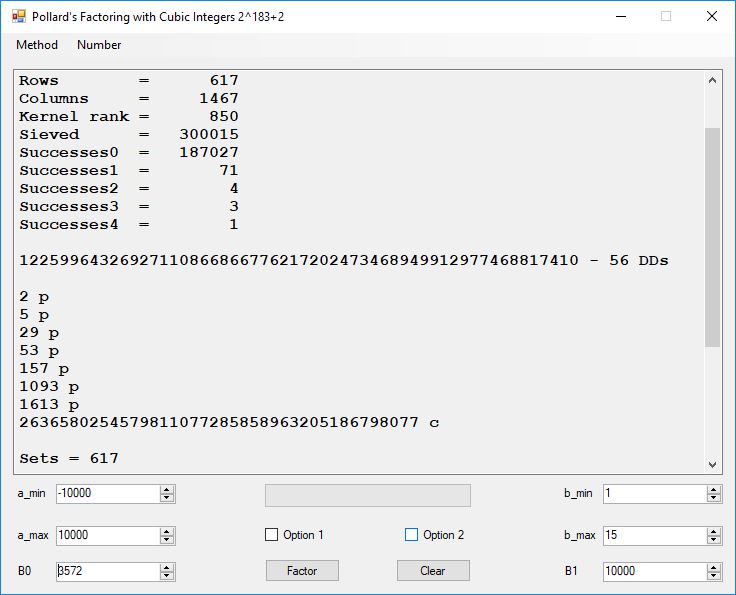

Typical full output from factoring with cubic integers:

A-Solutions = 973

B-Solutions = 234

Known Eqs = 614

Solutions = 1821

Rows = 1821

Columns = 1701

Kernel rank = 423

Sieved = 326434

Successes0 = 200863

Successes1 = 47073

Successes2 = 2708

Successes3 = 973

Successes4 = 1735

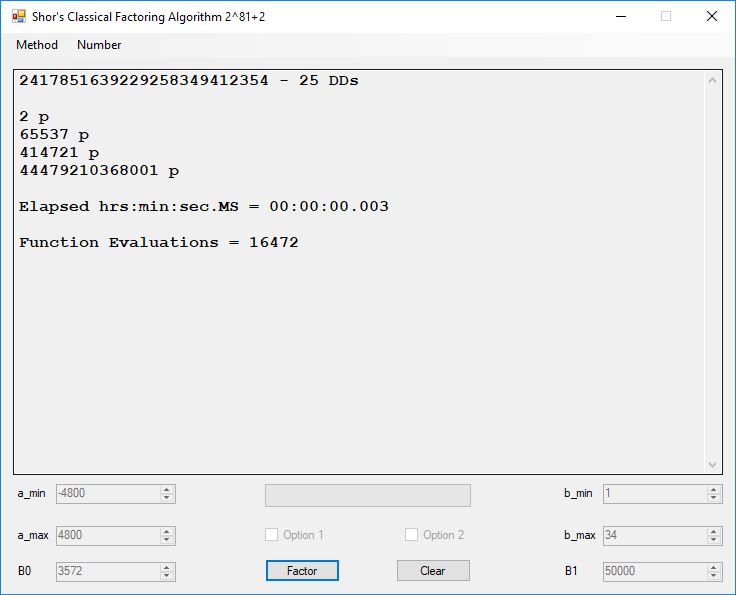

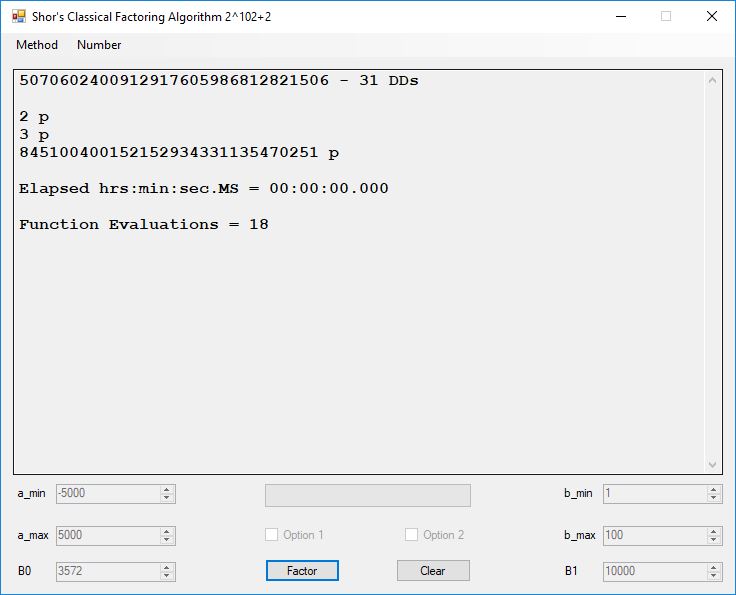

2417851639229258349412354 - 25 DDs

2 p

65537 p

414721 p

44479210368001 p

Sets = 189

#Factor Base 1 = 501

#Factor Base 2 = 868

FactB1 time = 00:00:00.000

FactB2 time = 00:00:05.296

Sieve time = 00:00:17.261

Kernel time = 00:00:06.799

Factor time = 00:00:02.327

Total time = 00:00:31.742

A-solutions have no large prime. B-solutions have a large prime between B0 and B1 exclusively which is this case is between 3272 and 50000 exclusively. The known equations are between the rational primes and the cubic primes and their associates of the form p = 6k + 1 that have -2 as a cubic residue. There are 81 rational primes of the form and 243 cubic primes but we keep many other associates of the cubic primes so more a and b pairs are successfully algebraically factored. In out case the algebraic factor base has 868 members. The rational prime factor base also includes the negative unit -1. The kernel rank is the number of independent columns in the matrix. The number of dependent sets is equal to columns – rank which is this case 1701 – 423 = 1278. The number of (a, b) pairs sieved is 326434. Successes0 is the pairs that have gcd(a, b) = 1. Successes1 is the number of (a, b) pairs such that a+b*r is B0-smooth or can be factored by the first 500 primes and the negative unit. r is equal to 2^27. Successes2 is the number of (a, b) pairs whose N[a, b] = a^2-2*b^3 can be factored using the norms of the algebraic primes. Successes3 is the number of A-solutions that are algebraically and rationally smooth. Successes4 is the number of B-solutions without combining to make the count modulo 2 = 0. Successes3 + Successes4 should equal Successes2 provided all proper algebraic primes and their associates are utilized.

Note factoring with cubic integers is very fickle with respect to parameter choice.